We all have sensations.

But sensations are not feelings.

So why do we confuse them?

Some sensations or bodily experiences such as sweaty palms, blanking out, hot flushes or a tightening in the chest are automatically associated with feelings. We are quick to confuse our experience of a sensation with these feelings. Why is that?

When we have sensations like tightening of the chest, we call upon ourselves to immediately make meaning of them. We have been socialized to give them names. So we assign these kinds of sensations specific feelings, such as sadness, fear, anger, guilt, and so on. And then we judge the named feelings to be either positive or negative depending on the names/frames we have given them. So even before these sensations have a chance of getting sensed/seen/heard/felt they have already been framed, named, and categorized.

But what if we were going about this all wrong? What if every time our heartbeat increased or our chest felt tight it couldn’t possibly mean the same thing? How can we really be sure of what it is we are actually experiencing? What is going on? What if we didn’t jump to think that a tightening in our chest was negative but rather stayed in the zone of listening and being curious about all the possible ways it could be made sense off?

We have the ability to go on in our daily life with unnameable experiences. But in sharing it, we typically have to call it something. Why not just say I feel sweaty or tight-chested? Why do we name it as nervous or scared? By naming our sensations, do we feel we are better able to move on, than by calling the sensation by its description, something like sweaty palms?

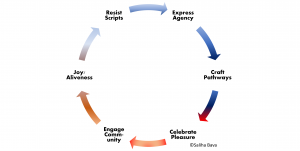

I draw on social communication theorist John Shotter who calls it the “felt sense… of a yet unknown something…which has not yet been given adequate linguistic expression.” There is actually no benefit in rushing to give these sensations linguistic expression of feeling. Instead, try simply using the words which describe it, if needed. Be with it. Talk with it. We can choose to be tentative, let it have air to breathe. We can experience how it seeks to be expressed before we run in to name it and fix it. Naming is one of our most powerful tools to create meaning. But naming a racing heart as nervousness versus excitement changes the meaning. The activity of naming it one way and not the other is a creative activity. It is how we create possibilities for ourselves.

Naming provides the benefit of organizing our experiences. In so doing, it categorizes things/events, potentially reducing complexity and helping us to move forward in life. But naming also has the potential to reify or to treat something that is abstract as if it exists as a real and tangible object. Alfred Korzybski, Polish-American philosopher stated, “the map is not the territory.” That is, the name is not the sensation. Rather the name is what we have created to point towards that sense, as a way to mark its presence. We experienced a tightening of the chest. The name we gave it is nervous or panic. The sensation has passed and the name, panic, in this case, stays on, takes on a life of its own. And we have created something that is now bigger than the sensation of a tight chest.

What might have been excitement or expectation is now panic.

So what do you say we instead choose to play with naming our sensations or the meanings we give to them? What if we stay with the unnameable and dance with it and continue to live life forward recognizing what Kierkegaard believed and I paraphrase, ‘we live life forwards and make meaning backwards.’

To learn how to play with your sensations and expand possibilities in your life contact me.

Photo by form PxHere